NOTE: This is Part 4 of a 5-part series. Read more with Part 1 (intro), Part 2 (anger), Part 3 (fear), Part 4 (sadness), or Part 5 (hope).

We’re continuing on this week, exploring how I use drawing to experience and process the emotions of Anger, Fear, and Sadness. Today, we’re sliding into our final emotion: Sadness.

Sadness: How We Feel It

The psychologist Paul Ekman says:

“The universal trigger for sadness is the loss of a valued person or object.”

We all have experience with loss. Sadness emerges after big losses such as a death of a loved one or rejection by a partner. But it also arises out of more abstract losses such as a move, a job change, or a goodbye. And sadness appears in the wake of even more ambiguous losses such as loss of identity, purpose, or expected outcome.

Sadness comes in varying states of intensity depending on the level of loss. We have all felt disappointed, discouraged, or distraught at times. Most of us have also experienced the more intense states of sadness: hopelessness, resignation, despair, even anguish.

(Note: I originally planned on including grief here as part of sadness, but after researching and writing about both, I’ve realized that grief is quite complicated and distinct from sadness. So I decided to split grief off into its own essay/series/class to give it the focus it deserves.)

Coping with Sadness

When faced with a loss and its ensuing sadness, we often try to cope with one of the following methods: withdrawing, ruminating, or self-medicating. But, while those techniques might initially work—by distracting us from the present moment—they end up prolonging our pain and suffering in the long term.

If it’s not processed and coped with, sadness can lead to loneliness, disconnection, and ultimately, depression. When we fall into sadness, we often back ourselves into a state of self-preservation. We need to connect with others, but our instinct to protect ourselves takes over. So instead of reaching out and getting support, we lock ourselves down, isolate, and numb.

Though that may all sound pretty dark, sadness is not a negative emotion. Researchers believe the purpose of sadness is to encourage us to re-evaluate our lives and make changes after a loss. It is also a signifier that we need help and support from others and, when processed, cultivates compassion and empathy for ourselves and others.

Sadness in Art + Music

I believe sadness is the emotion most closely tied to art—both art making and art consumption. It’s possible that’s because I also believe sadness is the emotion I struggle with (or have experience with?) the most. I have Major Depression and have been on and off medication for it and in and out of therapy for it. But I know that the emotion of sadness itself is not the problem.

When I successfully process and cope with my sadness, it becomes a pathway to feeling more connected with myself and others. Feeling sad reminds us that we are human and that suffering is part of being human—that we are not alone.

Perhaps that is why we are collectively drawn to “sad” art. There is something astounding about seeing a painting, watching a movie, or hearing a song that perfectly captures how you feel when sadness haunts you. Art can do that with other emotions, sure. A song can feel happy or angry. But there’s something visceral about a sad song or a sad movie—somehow it digs deeper into our hearts.

Take, for example, the song “The Sixth Station” composed by Joe Hisaishi for the movie Miyazaki movie, Spirited Away. Take a listen here:https://www.youtube-nocookie.com/embed/VbRmFSQYeac?rel=0&autoplay=0&showinfo=0&enablejsapi=0

Doesn’t that song make your chest ache? And yet, it’s beautiful. I want to listen to it. Perhaps the reason we are drawn to sad music and movies is not that it makes us feel sad (who actually wants that?), but because we know the artwork was created by an artist—a person who has felt the way we have. For an artist to create something that can tap so precisely into our heart, they must have been where we have been. They have felt the sadness that we have felt. And, as their artwork is evidence, they made it out of that dark hole. They were able to sit in their sadness, feel it and process it, and transform it into something new. They took the feeling they were feeling and pulled it out of themselves—not to get rid of it, but as a way of embracing it and sharing it with others as a tangible piece of art.

It’s one of the most powerful things there is.

And so, I’ve arrived at the same point I’ve come to with all three emotions in this series: if we can recognize when we feel sadness, and allow ourselves to fully experience it and accept it, then we can consciously choose how we want to react.

We can listen to our sadness as it tries to show us what we have lost and what we value. Rather than locking ourselves down, we can allow sadness to open us up—to accept changes in our lives and cultivate a deeper connection to the humanity inside ourselves and others.

And so, that’s where drawing our sadness comes in.

Sadness: How to Draw It

Now that we have more of a grasp on sadness and what it feels like, let’s explore how to draw when we’re sad.

When I’m feeling emotional, I like to take a moment to sit down at my desk and think: If I were to draw right now, how would I want to draw? What way of drawing do I feel pulled towards? What way of drawing feels doable in this moment? With sadness, I’ve discovered a couple of specific answers to those questions.

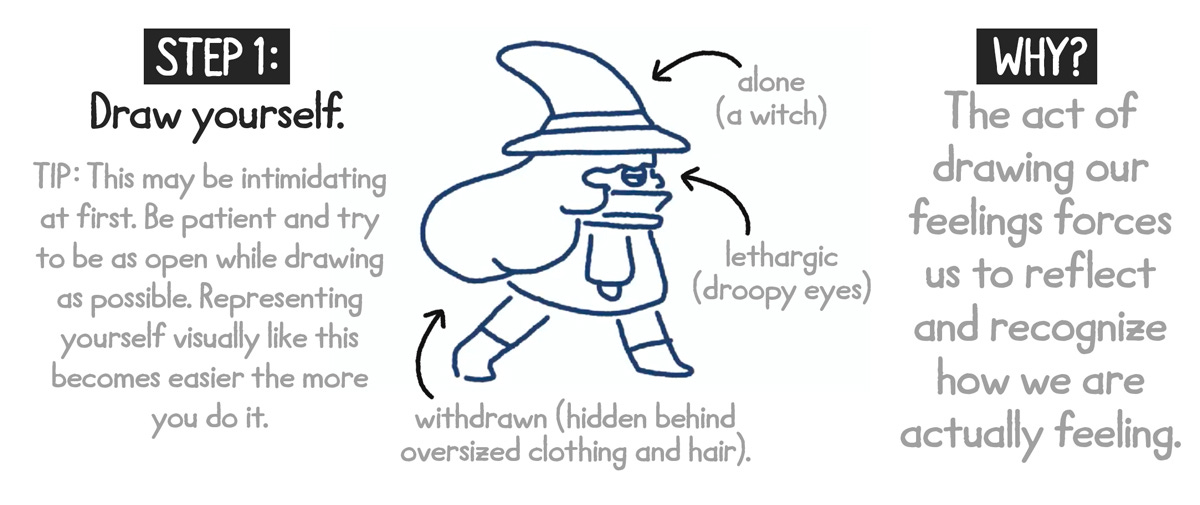

First, when I’m sad, I feel a desire to draw myself. In the other emotions I’ve covered, my drawings were not direct depictions of myself. But in sadness, I feel pulled to draw myself. This may be a form of personalization—the belief that I am the problem, the one to be blamed for the situation, loss, and sadness. It seems drawing myself helps alleviate that blame, as it usually ends up making me feel a bit lighter and more at peace. Perhaps seeing myself on the page as a character allows me to see myself with more self-compassion or empathy as if I were someone else. So the process of drawing myself and seeing myself visibly on the page is a powerful way to get out of a downward spiral.

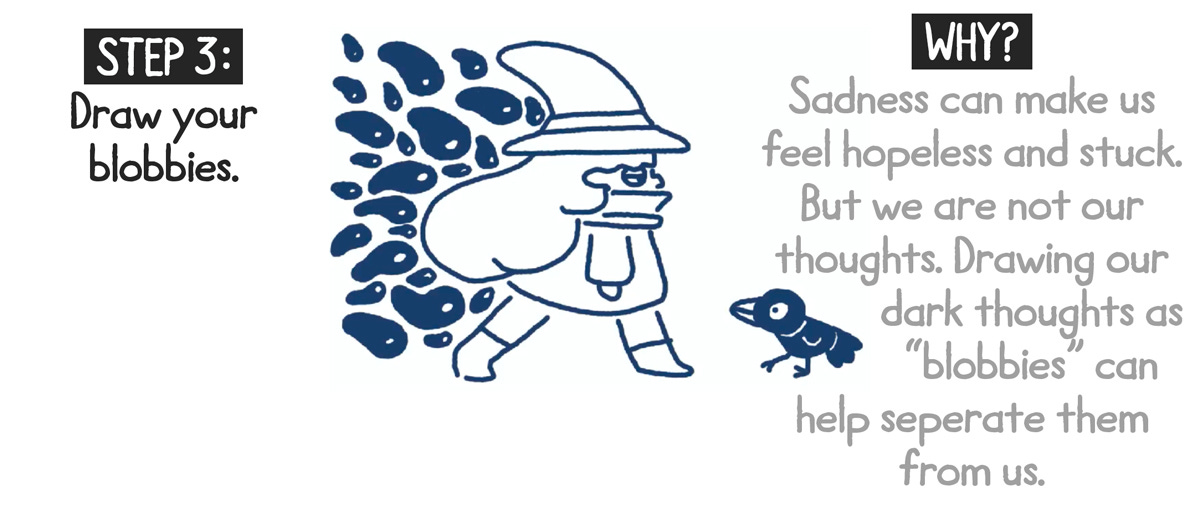

Second, when I’m sad, I feel a desire to draw my darkness (blobbies). Everyone has darkness inside them—negative thoughts, harmful beliefs, and that mean inner voice. It’s that darkness that pulls us back down deeper into sadness. Some people call them inner demons, but that feels too harsh to me. I’ve come to realize that darkness is just a part of human life and it doesn’t have to be a scary demon that we run away from. To me, it’s more helpful to see them as things we have to learn to live with. So instead, I call them blobbies. And when I’m feeling sad or depressed, drawing those blobbies brings them out of the darkness into the light—out of my head and onto the page. Drawing those dark thoughts and feelings as little blobby creatures transforms them from intense and debilitating beliefs into something more approachable and almost silly. It makes them feel more manageable.

And so, with those two insights in mind, I’ve developed my own method of drawing that allows me to experience and process my sadness, and I call it… Me and My Blobbies!

Drawing: Me and My Blobbies!

To show you how and why drawing Me and My Blobbies helps me process my sadness, I’m going to break down the drawing above that I created recently when I was feeling sad.

For context: I drew this in January, about two weeks after the holidays (which were difficult this year) and I was desperate to have some alone time with my two-year-old daughter, Butterbean, back in school. But that was right when the highly contagious Omicron hit our town and after a series of possible exposures and school closures, she was in school for only 3 1/2 days in January. None of us ended up getting sick (thankfully!), but I was disappointed about not getting that much-needed time to myself. Each exposure meant we couldn’t go out and couldn’t get help for the next 5+ days. After 3 in a row, I was grumpy and exhausted. With every hit, I became more discouraged and more resigned. (A relevant side-note: we also made the regretful decision of moving Butterbean to her toddler bed in early January, and the transition was not easy—more crying and less sleep.) It felt like Covid—and everything else—would never end. After saying the ambiguous “I’m overwhelmed” for weeks, I finally realized I was sad.

And so, I took to my iPad to draw Me and My Blobbies.

The Aftermath

Drawing Me and My Blobbies is not a magic spell and doesn’t make difficult situations and emotions go away—but that’s not the point. The goal of drawing our sadness is to help us experience and express that sadness, so we can then consciously choose how we want to react.

Before I drew, my automatic response to my sadness was to deny and withdraw. My family is healthy and I’m fortunate to have a flexible job, allowing me to care for Butterbean when she’s not in school. I’m also lucky that Butterbean is a joy to be around—though, like any two-year-old, she has her meltdowns. So the thought becomes: What do I have to be sad about?

And that denial of our sadness is a dangerous game. There are levels of loss and levels of sadness, but just because your current sadness is maybe not as intense as someone else’s does not change the fact that you are sad. Criticizing, blaming, and shaming ourselves for our sadness only leads to more pain. And that’s where I was at: denying my sadness and withdrawing from… everything.

After drawing Me and My Blobbies, I was better able to see my sadness and accept it. Once I allowed myself to spend some time with it, feeling that sadness while drawing, it was much easier to accept it and decide how to move forward. I realized I had lost the expectation of time to relax and process the difficult events of the holidays. And from there, I was able to see my negative thought patterns and adopt healthier, more helpful thoughts. I was able to remind myself that this was most likely the peak of Omicron and that Butterbean would soon be able to go back to school. And, now that I knew exactly what it was I had lost, I recognized that I could actually make changes in my life to address the issue. Here and there, I was able to carve out chunks of alone time for myself even with a two-year-old at home.

And, after I had accepted and adapted, I was able to reach out to others. I set up a date night with my husband, and we vented about how difficult January was. I set up a virtual Zoom call with some artist friends to draw and talk together. Over sketchbooks and cups of tea, we shared all that we were struggling with.

Those moments of connection didn’t alleviate all my sadness or make my problems go away. But they reminded me that I’m not alone and that right now, many of us are struggling with Covid, parenting, and getting time to ourselves. And ultimately, that feeling of connection is what makes the sadness lift—knowing that I have listened to the sadness, realized what was lost, accepted the sadness, and taken actions to adapt to the loss.

Final Thoughts on Drawing Sadness

I’m glad I’ve been able to analyze and distill this drawing technique down into a relatively simple process that I can return to again and again. It makes it easier for me to recognize when I’m sad and makes sitting down to draw at that moment more approachable because now I know exactly what to draw—Me and My Blobbies.

We all suffer losses and feel sad sometimes. And that’s ok! But I hope the next time we feel sad, instead of withdrawing or ruminating, we can take a moment to draw Me and My Blobbies about it. Then we can truly feel our sadness, see it, experience it, process it, and move on to reacting in a healthy and helpful way.

I hope you enjoyed the third emotion of our series—thanks for reading! :)

<3,

Christine

Read more with Part 1 (intro), Part 2 (anger), Part 3 (fear), or Part 5 (to come).