The other day I was listening to the song, Home by Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros, thinking about what a wonderful song it is. If you haven’t heard it before, it’s a love song written and sung by bandmates Jade Castrinos and Alex Ebert.

Many songs are fictional storytelling. But this song comes across as real. We can feel the powerful bond between these two people, and they even address each other using their real names in the lyrics.

Here are a few lyrics to give you an idea:

“…Laugh until we think we’ll die

Barefoot on a summer night

Never could be sweeter than with you (hey)

And in the streets you run a-free

Like it’s only you and me

Geez, you’re something to see

Oh, home, let me come home

Home is wherever I’m with you

Oh, home, let me come home

Home is wherever I’m with you”

Q: How Do We Love?

When this song came out in 2009, I knew at the time that the two songwriters and singers, Jade and Alex, were dating in real life. And it made the song feel even more meaningful. It made me think, “Wow, yeah. That’s what love is supposed to feel like. They must really know what they’re doing and have the best relationship!”

Flash-forward to 2021. I heard this song again and was told that the couple had broken up years ago, and that Jade had even been asked to leave the band.

Now, forgive me for morphing back into sappy-teenage-fan-girl, but doesn’t that make you sad? Doesn’t it change the way you think about the song?

Home had been written by two people so deeply in love, as their way of professing their love to each other, right? So they had a movie-perfect relationship, right? How could they have written such a profound song about love, and then… break up?

Q: How Do We Live Compassionately?

I’ve had similar thoughts about other artists in the past, beyond singers and love songs. A recurring one that comes to mind is David Foster Wallace. I love his writing and have read practically all his books and essays. I’m fascinated with the way he thought and, in his nonfiction, his philosophies of the world and how we should live.

His essay, This is Water, which was originally a college commencement speech, hits me especially hard. It shows how David had the unique gift of seeing our true human nature and why we act the way we do. He spoke so much wisdom about the human condition and how (and why) we should live more compassionately.

But, as perhaps you know, he died of suicide in 2008.

So again, I asked myself: how could this person who was so in tune with human thought and had such wise advice about how to live… how could this happen?

Do Artists Have the Answers?

I’ve been thinking about this tension inside artists for a while now. And, though I am certainly nowhere near the artistic genius of Edward Sharpe & The Magnetic Zeros or David Foster Wallace, I feel that odd tension inside myself as well.

I write about the creative process and I teach art classes, and I’ve been told that what I say is helpful, occasionally even profound. And yet, I still struggle with many, many things. Sometimes the same things I’ve written about. I write about how to overcome creative block, but I still get creative block.

Thinking about this push and pull of questions and answers from my own perspective made me see the tension in other artists differently. And it got me thinking more deeply about why artists make the art we do.

Non-artists tend to assume that an artist—for example, a writer—chooses to write a book because he has the answers. She writes a marriage story because she knows what it takes to maintain a good (or bad) marriage. He writes a story about parenting because he knows how to be a good (or bad) parent. There’s a question and the artist answers it.

But I think that’s actually not the case for most artists or most artworks.

…Or Just the Questions?

We create art because we are searching for answers. We have questions—big questions—about life, love, and being, and we don’t know how to answer them. We feel some inner drive to explore and unpack those questions.

And through the process of unpacking, we sometimes stumble upon nuggets of wisdom. And that’s what others see, read, and hear in our art. So then, they assume “wow, this writer/songwriter/artist is so wise—they really have it all figured out.”

But the reality is that recognizing a truth is very different than being able to implement it successfully in your own life. We artists are often very good at illuminating truths, but that does not mean we always live them out consistently ourselves.

Perhaps, as the ones actively searching for answers, artists are not actually the ones with more answers, but just the ones with more questions. Or perhaps we’re just so stubborn that we need to write to ourselves what we ourselves need to hear most. Or perhaps we’re just the ones struggling with these questions the most.

That’s why these essays I write dip so often into my personal experience. I struggle with a lot of things, and I don’t know how to deal with them. I don’t have the answers. But instead of giving up or letting them fester inside me, I try to explore the question itself. Sometimes it works and sometimes it doesn’t. Sometimes I have an epiphany that changes the way I approach life or art completely. And sometimes that epiphany fades away months later, and I’m back where I started, needing to learn the same lesson again and again.

But maybe, for the artist, that’s kind of the whole point. If I had all the answers, I probably wouldn’t have this intense drive to keep writing and drawing and making things. We are continually unpacking questions and searching for answers.

Q: How Do We Live?

Hayao Miyazaki is coming out of retirement to make one last movie, titled How Do You Live. The movie is based on the Japanese children’s book of the same name, which, as you might guess, attempts to answer the question with philosophy and storytelling. The plot takes place in Japan in the 1930s and centers around a boy and his uncle. The boy’s father died early and asked the uncle to ensure his son grew up to be a “great man”, which to him meant “a fine example of a human being.” And through the uncle’s and boy’s discussions, that’s what the book aims to do as well. The author, Genzaburo Yoshino, attempts to answer the question ‘how can we be fine examples of human beings?’

We can assume that when Yoshino began writing this book, and probably after finishing it as well, he was not totally sure he had the answer. His book attempts to unpack the question and explore the concept, but in the end, it is up to you the reader to decide. Fittingly, the very last line of the book is, “How will you live?”

Miyazaki seems to see it this way too. When a journalist discovered the name of his next movie was How Do You Live, he asked the same question we all thought: “Will you give us the answer?” But of course, Miyazaki said, “I am making this movie because I do not have the answer.”

Perhaps that’s what makes a truly great piece of art. The artist has a deep question and the piece of art is merely a recording of their journey to answer it. Sometimes they find insightful wisdom, and sometimes they don’t.

But ultimately, the point of art isn’t to provide you with the answer, anyways. Instead, the artist is preparing you and encouraging you to explore, unpack, and answer the question for yourself.

P.S. One Additional Note…

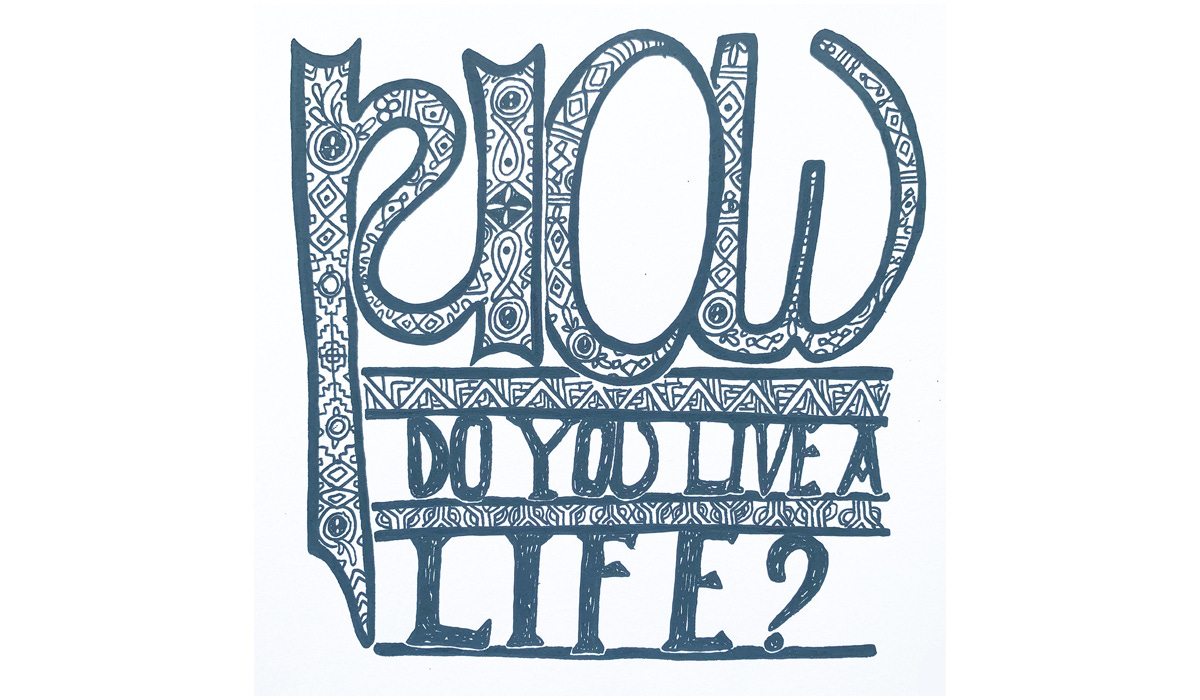

After writing this essay, I remembered this drawing I made a few months back in the trenches of my break/burnout/whatever-it-was. At the time, I was exhausted and confused and desperately searching for answers. And so, as we do, I turned to art and artists for help. But the thing is, I was so lost I didn’t even know what question I was trying to answer.

This particular drawing above was inspired by the Book of Kells, a book of illuminated manuscripts of the four Gospels from the New Testament. This beautiful, intricate book was painted and lettered by Columban monks, who lived full-time in an abbey, studying religious texts and creating art from their messages. I thought to myself, ‘surely, these monks know how to live!’ (In my existential flailing around, I also went through this same thought process with a slew of Buddhist texts.)

Of course, I was inevitably frustrated that they did not give me clear and direct instructions on what I should do. But looking back, now that I’ve written about this whole question/answer idea, I can see that those illuminated manuscripts were doing just what I’ve described here in this essay. The monks were not trying to hand out clear and simple answers—they were attempting to gently nudge me towards the questions I needed to be asking and exploring for myself.