George Orwell is best known as for writing the books Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, both published in the 1940’s. But in addition to his dystopian stories, he also wrote many essays on language, the craft of writing, and his concern about where writing and language was headed at the time.

Good ol’ George and I tend to align on many philosophies, and many of his thoughts on writing can be applied more broadly to drawing and art making in general.

Orwell’s Work

Orwell’s novel, Nineteen Eighty-Four hinges on the importance of language, writing, and literature. The book involves a Big Brother scenario where the top tier of society controls language, restricts vocabulary, and ultimately limits discussion and even thoughts in an effort to control society.

“If people cannot write well, they cannot think well, and if they cannot think well, others will do their thinking for them.”

–George Orwell

Prior to Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell published Politics and the English Language, a nonfiction essay on writing. We can see now how this essay was a precursor in his mind to creating the fictional dystopia in Nineteen Eighty-Four. In both the essay and in Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell is concerned about the deterioration of writing and language.

“Most people who bother with the matter at all would admit that the English language is in a bad way, but it is generally assumed that we cannot by conscious action do anything about it.”

–George Orwell

Orwell’s Six Rules for Writing

Of course, Orwell thinks we can do something about it and as part of that belief he presents his six rules for writing. They’re quite good.

“But one can often be in doubt about the effect of a word or a phrase, and one needs rules that one can rely on when instinct fails. I think the following rules will cover most cases:

–George Orwell

1. Never use a metaphor, simile, or other figure of speech which you are used to seeing in print.

2. Never use a long word where a short one will do.

3. If it is possible to cut a word out, always cut it out.

4. Never use the passive where you can use the active.

5. Never use a foreign phrase, a scientific word, or a jargon word if you can think of an everyday English equivalent.

6. Break any of these rules sooner than say anything outright barbarous.”

Aside from being good writing advice, I’m sure you know the part I love most about this list is that almost every line includes “never” or “always” but then the very last line is “break any of these rules” when necessary. Right on, George.

Aiming for Something Deeper

But Orwell wasn’t trying to tell everyone how to write or how to write the way he does. He was trying to get you—the writer, the artist—to think more deeply about how you write. And beyond that, and get super meta, he’s trying to get you to think about how you think when you write.

“These rules sound elementary, and so they are, but they demand a deep change of attitude in anyone who has grown used to writing in the style now fashionable.”

–George Orwell

Orwell is aiming for much more than a simple list of how to write well. That would be easy, and that has already been done. He’s not interested in that. He’s interested in how language and writing can affect how we think.

The essay speaks primarily about language used in politics, but it can easily expand beyond that. Orwell says he aims not only to focus on helping people learn how to get their point across—i.e. writing better—but instead on helping people learn how to cultivate a point worth making.

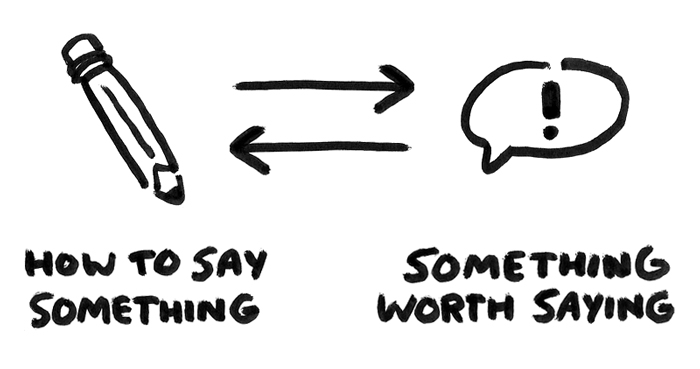

Having Something to Say

Orwell was focused on helping people write more clearly to communicate their ideas more clearly. But more than that, he was more intent on helping writers have something meaningful to communicate in the first place.

Just like me, Orwell is more fascinated and intrigued with the thinking, formulating, and nurturing of ideas, rather than solely the craft of art. We both agree that the ability to have and nurture a meaningful idea is more important than the ability to communicate the idea.

Before you can say something, you have to have something to say. And that applies whether we’re writing, speaking, drawing, or any other artmaking.

In Orwell’s essay, he applies this idea to politicians slinging around meaningless words, empty phrases, and incomprehensible gobbledy-gook that has the sole aim of sounding good. It’s dressing up a weak idea in different clothes. Or, in Orwell’s (better) words: “to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind.” He wants writers to stop focusing on how to say things, and instead start focusing on how to have things worth saying.

Drawing as Communication

And this concept applies beautifully to other crafts as well. We can focus on learning composition, shading, and perspective to be able to communicate elegantly and beautifully. But if we don’t have something meaningful to communicate, then what good is that ability to communicate?

We can learn how to say something, but we also need something to say.

Question Your Process

Orwell goes on in his essay to include a series of questions writers should get used to asking themselves while writing:

“A scrupulous writer, in every sentence that he writes, will ask himself at least four questions, thus:

–George Orwell

1. What am I trying to say?

2. What words will express it?

3. What image or idiom will make it clearer?

4. Is this image fresh enough to have an effect?

And he will probably ask himself two more:

1. Could I put it more shortly?

2. Have I said anything that is avoidably ugly?

The order of these questions is crucial. Orwell’s first question is “what am I trying to say”, it is NOT “what words will express it”.

In visual artmaking, like drawing, I think artists often begin in the opposite direction. They begin with what pen should I use, what colors should I use, what style should I use? Those questions are rooted in the realm of how to communicate, not what to communicate. Pens, colors, and style are all just ways to communicate an idea, not ideas in themselves. They are the tools we use to speak.

And they are secondary to the “something” we speak. Before we can say something, we have to have something to say. We have to first consider, “what am I trying to say?” before we can consider how to say it, write it, or draw it.

The Purpose of Art

What is the purpose of our art making? Why do we make art? And even more broadly, what is the purpose of any art making? Why does anyone make art?

I believe art’s purpose is to illuminate.

It’s a way to share, tell stories, and spread human truths. It’s a way to share your story, but only if you’re able to see, think about, and cultivate your story first.

Orwell’s stated purpose in art making—both in his novels and essays—was to use his art as a way to fight against totalitarianism. He saw language being used in the 1940s as a means of control and confusion, and he used his own writing to fight back. He urged writers to be more clear and simple, instead of complex but empty as was the trend back then. And he believed in order to write clearly, you have to think clearly first.

“The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. When there is a gap between one’s real and one’s declared aims, one turns as it were instinctively to long words and exhausted idioms, like a cuttlefish spurting out ink.”

–George Orwell

The Purpose of Our Art

And so, what is the purpose of your art? It doesn’t have to be as grandiose as Orwell’s. And you don’t always have to think about it so consciously. Eventually, the purpose will shine through and persist in everything you make, even without you being aware it’s working behind the scenes. It will happen when you start thinking clearly.

Each story we write or drawing we create can communicate something meaningful. Some will be big and important, like fighting fascism. Others some are small and incidental, like just saying your tired. What’s meaningful is up to you.

But beyond each piece, when all your art is seen from above as a body of work, an overall purpose begins to emerge. And once we find that overall purpose, it can serve as a guiding principle for what we’re saying in all our art. So we can automatically begin each piece not with “how will I say this” but with “what will I say”.

The Purpose of My Art

My purpose in art making has only recently begun to crystallize. I’m beginning to realize that my purpose has two parts. The first is to use writing and drawing as a way to think through and organize my thoughts and experiences into coherent beliefs and learnings.

The second is to use writing and drawing as a way to help others learn to do the same. To show them how to use writing and drawing as a way to think through and organize their thoughts and experiences into their own coherent beliefs and learnings.

These two purposes are what allow me to focus on what I am trying to say. They give me a point of calibration for the tools I use to speak, including these weekly essays, my daily sketchbook drawings, Might Could Studiomates, and Sketchbook to Style.

No artistic purpose is ever completely nailed down and figured out, because our art is constantly growing, evolving, and changing as more and more art is made. But having the ability to think about the meaningful-somethings we’re trying to say, can be the key to finding the right pathway to follow.

So, now you have some questions to ask yourself. Why do you draw? Why do you make art?

What are you trying to say?